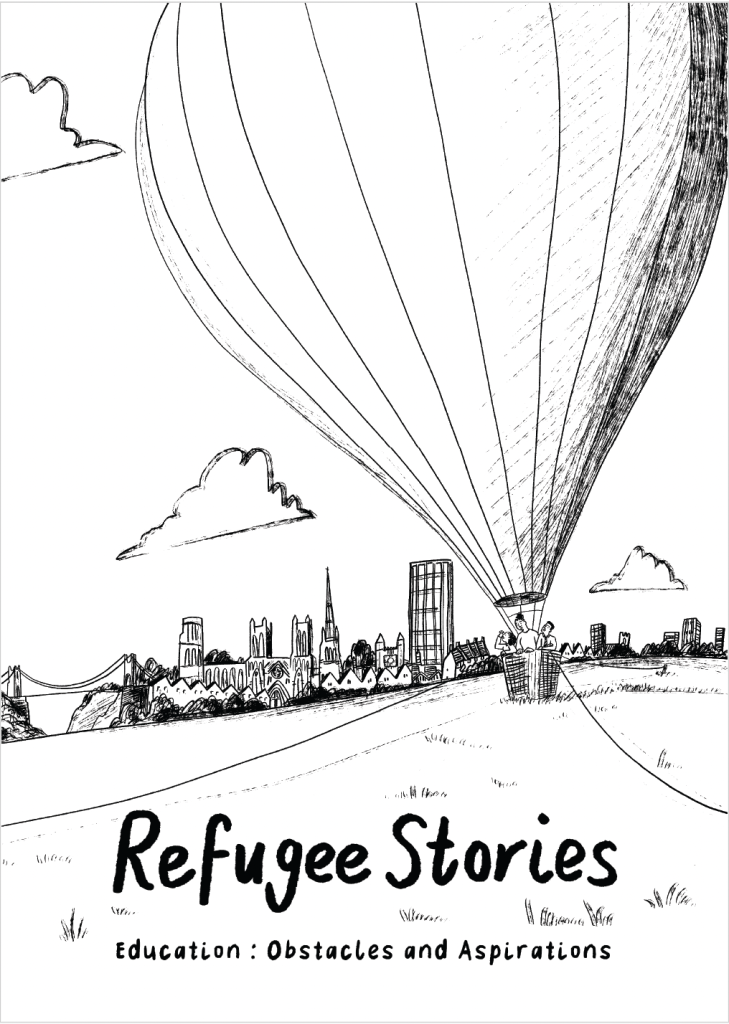

Refugee Stories: Education: Obstacles and Aspirations draws on findings from a doctoral research on young refugees’ educational experiences in England. The study investigated how young refugee people and their families have encountered the education system while considering the implications of living as refugees in England.

Young refugee people’s right to education is enshrined in British law; however, the UK has no specific educational policy for them.

Invisibilizing practices add to the silence around their experiences and needs. Refugee Stories tells young refugees’ and families’ stories to amplify their voices and shine a light on the social and material conditions they experience.

How Refugee Stories was born

I volunteered as an English as an Additional Language (EAL) tutor to young refugees at a secondary school in the South of England. I also volunteered at local organizations advocating for refugee people and fundraising to facilitate their access to phones and internet at home. Through volunteering, I built connections with three families who expressed interest in participating in my research. While most research tends to be school-based, I focused on working directly with families to understand how they encountered England’s education system. Particularly, I was interested in how policy meets lived experience. The mothers often asked me to help their children with their homework or to help them access technology to continue remote schooling. I maintained contact with families and provided support when they needed it throughout the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns implemented in England.

As part of my methodology, I enacted an ethics of care by trying to mitigate some of the challenges they endured. Refugee families, including asylum seekers, may have limited access to resources and technology at home. Therefore, remote schooling was very challenging for them because they did not have reliable access to computers, phones and internet, and they also struggled to pay for data for their cell phones. As part of my research and commitment to support them, I tried to highlight their hardships and amplify their voices, as in this article, I co-wrote with Maria, a mother seeking asylum who participated in the study.

Creating Refugee Stories with families to highlight their experiences and perspectives was essential to my methodology and ethics of care. My approach to critical ethnography was to go beyond simply observing and interviewing participants but also to try and address some of the hardships that families experienced. In addition to providing schoolwork and English language support, I facilitated one family’s access to a laptop and a phone, books and art supplies for all the young people, data for their phones and access to extra-curricular activities such as football lessons. I dedicated time weekly to helping one family use their new laptop and new software needed for their schooling, including MS Teams, sending emails, creating Word and PowerPoint files and attaching files to email messages. When their schooling shifted online, young people were expected to know how to do those tasks, but some had never done it before.

As a migrant from a working-class family from the so-called ‘global south’, I understood some of the challenges that the families lived through. We developed a connection of mutual care. The mothers often cooked meals and invited me to have lunch or dinner with them. One mother baked a cake for my birthday, and their children wrote me Christmas cards and ‘thank you’ notes.

Refugee Stories was part of my methodological approach to amplify young people’s and their families’ perspectives and experiences and communicate research findings beyond academia. It was an art-science collaboration to make research findings more accessible. For example, the young people chose their pseudonyms, the appearance of their characters and what they wanted to highlight to readers. Refugee Stories was funded by the University of Bristol’s Temple Quarter Engagement Fund, allowing me to involve families in creating the zine and pay them an honorarium for their time.

Refugee Stories for teaching and learning

I am interested in learning how educators and students may find the zine useful for their practices. I point to a few goals I have for how this zine may support learning in classrooms:

I adopt anti-colonial and anti-racist perspectives. The zine prompts us to consider how education can acknowledge the UK, EU, and US colonial histories and imperialism that permeates today, including the militarization of borders and the criminalization of migration. Colonial histories and imperial violence need to be acknowledged in education systems.

The zine could lead to discussions on what causes people to leave their homes, migration histories, how refugees are created, and the challenges they experience trying to find safety.

For example, Muhammad, a young Iraqi man portrayed in the zine, often talked about the history of Iraq and the US invasion of his country. Muhammad also highlighted that his history classes mainly studied Europe and World War II. While interesting, he wanted more history about the world, including Mesopotamia. Muhammad’s reflections indicate the need to challenge the Eurocentric nature of curricula in Western countries – what knowledge(s) and histories are erased? Whose voices are silenced?

The zine can provide resources that connect to students’ realities.

I learned from my research that curriculum content is often disconnected from young people’s realities. A young man from Eritrea in secondary school discussed that he had to annotate Shakespeare’s poems while learning to write for the first time in his third language, English. His teacher was aware that he struggled but was not aware why he faced difficulties to follow her instructions. She had no idea about his previous experiences, including that he had never been taught how to write. Resources like this one can offer mirrors of students’ own experiences, while offering windows for other students into refugee students’ lives.

The zine can support educators in understanding the knowledge refugee students bring to the classroom.

Moreover, schools may view refugee learners through a deficit-based lens and focus on what they ‘lack’: insufficient English language proficiency, no ‘formal education’, limited schooling or viewing learners through a lens of ‘trauma’. Young refugee learners bring essential knowledge(s) and different ways of knowing, being and doing. They may still be learning English but often speak or understand various languages. As demonstrated in Refugee Stories, young people are resourceful and active agents in creating their networks, helping their parents learn the language and their new country’s systems, and studying independently. England is very institutionally monolingual. Talking to the young people who participated in the study, I learned that some educators might have deficit-based views of families who speak their first language at home rather than English, thinking that the young people may struggle to learn English because they speak other languages at home. In this study, some young people were influenced by that and often stopped using some of their languages to prioritize speaking in English more often. Refugee Stories could be used to discuss various themes, language and multilingualism, migration, and colonialism.

I welcome your thoughts on these issues and how you may use Refugee Stories for teaching and learning.

Read Refugee Stories

Artist

About the author

Jáfia Naftali Câmara: I am a Brazilian scholar and Research Fellow at the Centre for Lebanese Studies, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. I hold a PhD in Education from the University of Bristol with a thesis titled “Refugee Youth and Education: Aspirations and Obstacles in England”, an MA in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages from New York University and a BA in English Literature, Criticism and Theory from the University of California, Davis.

My research interests centre on education in emergencies, the politics of education and the intersections between racism(s), border regimes and integration discourse and policy. I am interested in investigating the coloniality of education, migration policy and practice at national and global levels. Other research areas of interest include comparative research, knowledge production, education inequality and research partnerships.

My PhD research focused on how young refugee people and their families encounter England’s education system, using critical ethnography, interviews, observations and arts-based activities with participatory elements. I adopted critical, anti-colonial and anti-racist perspectives considering how education and asylum and refugee resettlement policies meet lived experiences in England.

I am currently undertaking a study on education in emergencies focusing on Brazil and Latin America.

Suggested citation

Temesghen, Olivia Sarah, Rivkah, Fatima, Muhammad, Amira and Maria. (2023). Refugee Stories: Education: Obstacles and Aspirations. (Edited by Jáfia Naftali Câmara). Refugee REACH, Harvard Graduate School of Education: Cambridge.